Plum Pie. Zombie Green. Yellow Bee. Purple Monster

by Jen Campbell

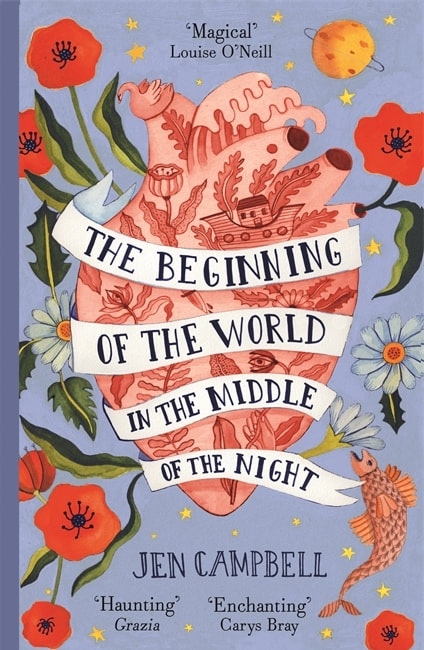

from The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night

When you grow up, who or what do you want to be?

Out on the road, Jack came across a man who said he’d buy his cow for a handful of magic beans. Five, to be precise. He said if Jack ran back home and buried them in his garden, a plant would grow there. A plant so tall it would make friends with the sky.

But what if Jack took those magic beans and planted them inside himself, instead?

Swallowed them down so they were hidden away inside him. Growing, growing, glowing.

Poppy lies down and covers herself in green leaves.

“Am I alive or am I dead?” She giggles, trying not to move her mouth.

“You’re both,” I say.

“Wrong! Wrong wrong wrong.”

She writhes on the ground like an animated rag doll. A sea of aquamarine. Ivy’s lounging in the tree house, wearing sunglasses shaped like clouds. Madame Honey wanders between the tents, covered in bees, ticking things off on her clipboard.

She pulls out a tape measure and lines it along the shoots poking out from Clover’s torso.

She scribbles down some numbers while Clover whistles, photosynthesising in the sun.

I count seeds in the palm of my hand.

One.

Two.

Tree.

Ok, bad pun. Sorry.

This summer, when they collected us from the train, Heath unfurled his hair, complete with twisting vines, and the buds swam along the path behind him like a bridal trail.

Jasmine used twenty face wipes to rid herself of the white paint clogging up her pores, and her green skin shone.

Daisy wouldn’t stop talking until the sun went down, and the young nocturnal ones sleepily chased their shadows across the lawn.

“Welcome to this year’s Camp,” Madame Honey’s smile was sickly sweet. “My, my, how big you’ve grown.”

That evening, we collected dead wood for a bonfire. We burned the coral petals Rose pulled from her mouth, presents from the plants growing quietly in her throat, and we told stories of our springs.

“I’m working at the greengrocer,” Heath told us. “Trying to save up money for a trip.”

“Where to?”

“I want to find the umdhlebe.”

“The umdhlebe?”

“It’s a poisonous tree that feeds on everything around it,” Heath said. “It hasn’t been seen in two hundred years but I bet I could find it.”

“Why would you want to find a poisonous tree?” Ivy snapped, hanging upside down from the tyre rope swing.

“Why not? I read a book that says botanists in South Africa found it, its soil fertilized by all the things it’s killed.”

“Cheerful!”

“What will you do with it when you find it?”

Heath looked a little embarrassed. “I don’t know,” he shrugged. “I guess I want to study it. See why it’s feared. Say hello. Perhaps sit with it for a while.”

Rose coughed and a tide of petals fell into the flames. In the smoke, I saw a lonely tree, the ground around it littered with skeletons.

Lily didn’t come back this year. No one got on at her stop.

We looked all over the train, including the dark damp corners, where she sometimes liked to hide.

When we arrived, Madame Honey said: ‘Lily’s parents haven’t returned our calls.’

And we all visibly wilted.

Lily was one of the best of us.

At the age of eleven, her hair turned white overnight and she started humming funeral songs.

That’s the year they brought her here.

She always smelled of peppermint.

Last August, she swallowed apple seeds behind the shower block and didn’t deny it when she was caught.

She was obsessed with html colour codes called hex triplets, and we rolled those across our tongues to try and taste the witchcraft. Soil up to our elbows, creating earth angels in the dust.

They say that when you grow up you shouldn’t have things like favourite colours because there are more important things in life. But that is bullshit. The two of us had competitions, reciting hex triplets by heart:

LightSeaGreen #20B2AA

MediumOrchid #BA55D3

OliveDrab #6B8E23

Thistle #D8BFD8

Seashell #FFF5EE

BurlyWood #DEB887

Tomato #FF6347

GhostWhite #F8F8FF

We’d spit colours into the woods so the trees could swallow them whole. We’d planned to colour code the world.

And now we don’t know where she’s gone.

We look for her in the undergrowth, and down by the stream. We scan the newspaper she used to love, in case she’s somehow made the headlines. While flicking through, the ink staining our finger tips, I remember the times we’d press flowers between the pages of a book of fables, trying to guess the type of tree it was made from. Pressing ourselves between the stories.

Ivy steals Madame Honey’s mobile phone and we try to find Lily on the internet, but we don’t know her last name, and time and time again search engines simply show us the flowers she is named after.

But Lily isn’t just a flower. Lily is our friend.

If Jack had taken those magic beans and planted them inside himself, he could have become one of us. He could have found himself in the headlines for different reasons, plastered to the side of Lily’s tent, where she used to stick all the important news.

A doctor in Beijing has found a dandelion growing inside the ear canal of a sixteen month old girl. It had partly flowered, and was said to be very itchy.

A Russian man, suspected of having cancer, was found to have a small fir tree growing in his left lung. When they took it out, he took it home.

Once, in Spain, a lily was found growing from the heart of a boy who couldn’t read.

We have always tumbled out of newspapers and myth. Hyacinths flowered from the blood of Apollo. Carnations bloomed from the tears of Mary. Snow drops are said to be the hands of the dead.

You have to find us between the lines.

How strange they think we are.

Madame Honey passes out chalk, crayons and felt tip pens.

“I want you all to sit and draw for thirty minutes,” she says.

“Draw what?” Clover scowls, her hair now peppered with flowers.

“Whatever comes to mind,” Madame Honey beams. “No conferring.”

So, we pick up some colours and we all draw Lily.

Sleeping Lily.

Dancing Lily.

Shouting Lily.

Tiger Lily.

Lily climbing up a beanstalk, her hair blending with the clouds. Lily locked up in a tower.

Lily talking with the trees.

Lily once told me that trees communicate underground. They share food via symbiosis and don’t tell humans that they’re doing it.

“You just think you’re looking at a forest, when you look at a forest,” Lily said. “But that’s not it, not really. The trees are talking. You can’t see it, but they’re talking. Forests aren’t terrifying places. They just speak a different language.”

ForestGreen #228B22

“Come on, Fern,” Jasmine nudges me. “You’re the storyteller. Where do you think Lily is?”

Well. Once upon a time, a king and queen were trying to have a baby. They tried for a long time, but each time the baby died. Then, many years later, the queen fell pregnant again. This time, she felt sure that things were different. She craved food she’d never tasted before: pickled seaweed, sour radishes, honeycomb and even flowers. One of the flowers the queen loved to eat was the Rampion Bellflower, also known as the Rapunzel, but it didn’t grow anywhere in the palace gardens. It grew just outside them, in a secluded patch of earth, over the palace walls.

Every night, the queen begged the king to climb over the wall at the edge of the garden, to pick the Rapunzel flowers glowing under the moon. He carried them home piled on top of his crown. The queen chewed them as the sun rose, and brewed some petals in her tea.

One night, when the king was out collecting Rapunzels, a fairy appeared.

“Those are my flowers,” said the fairy.

“But I am the king,” said the king. “And I own everything in this land. Besides, my pregnant wife craves them.”

“Then you may take the flowers but, in exchange, you must give me your child.”

“Fine,” said the king, thinking the fairy was being ridiculous. “You can have our baby. Come and collect her when she’s born, if you think you’re brave enough.”

So the fairy did. And the king discovered he was bound by magic to give her his child. The child was named Rapunzel, and the fairy locked her in a tower for she was jealous of her hair. It grew long like vine and she braided it with bracken. She hung it out of the high windows for everyone to see.

Her genes mixed with the flowers her mother had consumed. Part girl. Part plant. Raised up above the world...

“Are you saying that Lily has been stolen by a fairy?” Poppy asks, sipping Miracle-Gro.

“There’s no such thing as fairies,” Ivy spits. “Don’t be stupid. The government’s probably taken her away. I bet they’ve put her in isolation. For experiments.”

“We don’t know that!”

“Oh, yeah? Well, where do you think she’s gone them, huh? Where exactly did she go?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps she ran away.”

Lily was not a wallflower.

I always thought of her as a waterwheel plant, a carnivorous green that could breathe underwater, propelled through the waves. A water Lily. A plant like the Aldrovanda, which doesn’t have roots. It’s free-floating and traps whatever gets in its way, like a Venus Flytrap.

Lily was like that. Lily took no shit.

At the end of each summer, when the first leaves would fall, and they’d come at us with pliers for cuttings, Lily never went quietly.

“It’s not ok, Fern,” she yelled, as they grabbed her by the wrists. “It’s not ok for them to do this. It’s not ok, it’s not ok, it’s not ok.”

The first few weeks at Camp are always the easiest. We catch up, we let them measure us. We accept the Miracle-Gro and drink as much water as they put in front of us, and we let ourselves blossom in the sun. It’s such a relief not to have to hide away. No one’s pointing at us in the street, no one’s refusing to serve us at the supermarket. Here our differences can be prized, noticed and admired.

Ivy, all six foot seven of her.

Poppy and her hypnotic eyes.

Rose with her plants flowering in her throat.

Clover with her good luck vines sprouting from her chest.

Jasmine with her sea green skin that doesn’t fade in winter.

And Heath, who embraces his pale pink flowers. They go by the name of Erica. He calls them the other half of his soul.

But now the summer is ending, and the September wind is here.

“Lily used to think that we could cross-breed with other plants, if we swallowed certain seeds.” Poppy says. “She said if we became more than one thing, it would make us even stronger.”

“What, cross-pollination?”

“Isn’t that what they say about breeding dogs? Mongrels, and stuff?”

“You better not be calling me a dog.”

“Aren’t we already cross-breeds?” Rose hiccoughs. “I mean, we’re already more than one thing.”

How To Cut A Rose for Winter

1. Begin pruning from the base.

2. Always prune dead wood back to healthy tissue.

3. Remove any weak branches.

4. Roses have a habit of spreading. Keep them under control. 5. Cuts must be clean, so keep your secateurs sharp.

When Madame Honey disappears, as she does at the end of every summer, and the tree surgeons take her place, with sharp tools and needles, feeding tubes and weed killer, we are ready.

Ivy and Clover use their vines like extra limbs to prise open the doors of the laboratory, and we all race in. Daisy gasps. It’s humid in there, with moisture clinging to the windows, and we see ourselves inside, lining all the shelves. All the cuttings they’ve taken from us, growing artificially in glass cages. Parts of our bodies labelled. Poised, sterile and dull.

We smash the glass. We grab ourselves. We run.

Oh, how we run.

Packets of seeds slide across the vinyl floor and jolt at every pot hole.

“Tell us another story,” Heath pleads, as we pull out onto the motorway. Ivy bent over the wheel of our stolen van and us huddled in the back, our arms filled with green light.

Ok. Once there was a creature called a lilit. Lilits appear across the world, ducking and diving through history and culture. But wherever they crop up, they are night spirits. Demons, whose souls are trapped in the abyss. Once, a god reached for a lilit and a woman called Lilith appeared. A witch, with a will of her own. But she didn’t look the way men wanted her to look, and she didn’t do the things they wanted her to do. So they cast her out into the night, where she bore children in the dark. Strange children. Fantastical children. Children with names pulled out from the soil.

Ivy revs the engine and the wind trickles in through the cracked windows of the van.

Every so often, we pull into fields and duck into forests, where we plant parts of our rescued selves.

They shiver pleasantly in the night-time air, surprised to find themselves in the wild.

“How long do you think it will be before they catch us?” Jasmine asks, peering out at the road behind us, where the sky is turning firebrick and coral.

I shrug, hoping its long enough to spread ourselves far and wide.

Out on the road, Jack came across a man who said he’d buy his cow for a handful of magic beans. Five, to be precise. He said if Jack ran back home and buried them in his garden, a plant would grow there. A plant so tall it would make friends with the sky.

But what if Jack took those magic beans and planted them inside himself, instead?

Swallowed them down so they were hidden away inside him. Growing, growing, glowing.

Jasmine tears open packets of seeds and pours them into our waiting hands. We cup them like grains of sand. Tip them into our mouths and swallow.

At the next petrol station, I find a stamp, crumpled at the bottom of my rucksack. We all scribble a letter on an empty packet of tulip seeds, addressed to Lily’s favourite newspaper, requesting to place an advert in the hope that she might see it. We argue over what it should say. I want to send her a secret message in html colour codes. #7D0541 #CFECEC, which means ‘Bullet Shell’ and ‘Pale Blue Lily,’ to let her know we’re fighting and we hope she’s fighting, too.

“She might see it and think we hope she’s dead,” Ivy says. “Bullet shell sounds aggressive.”

“What do you suggest, then?”

Rose raises a timid hand. “Why don’t we just list her favourite colours? To let her know she’s on our mind?”

So that’s what we do.

Our version of Morse code.

Lily, we love you. We hope that you are thriving. x

#7D0541 #54C571 #E9AB17 #461B7E

(Plum Pie. Zombie Green. Yellow Bee. Purple Monster.)